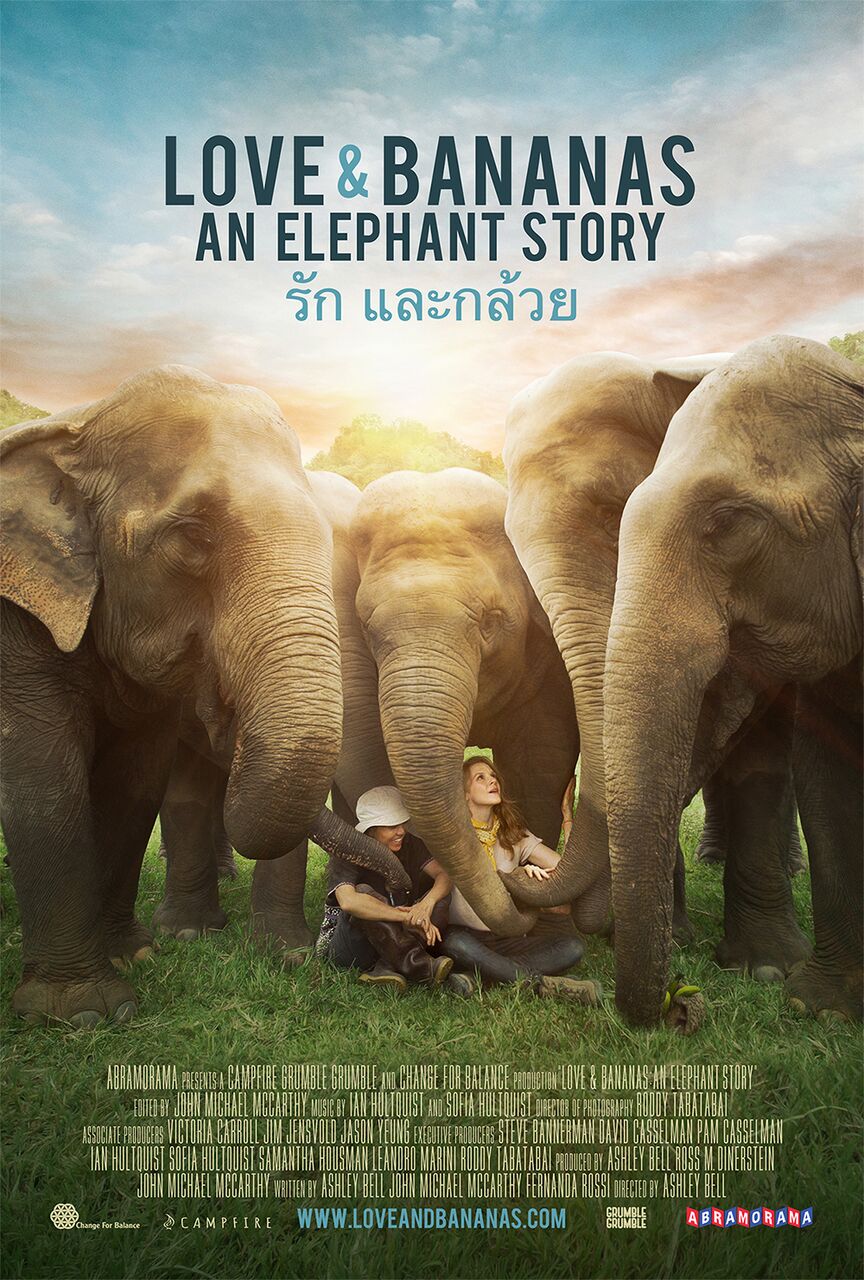

Filmmaker Ashley Bell Documents the Plight and Hope for Asian Elephants in “Love & Bananas: An Elephant Story”

By Angela Dawson

Actress Ashley Bell is best known for portraying a young woman possessed by the devil in the horror franchise “The Last Exorcism.” And now the native Angeleno confronts another type of evil, an atrocity against nature committed by man, in a documentary she produced, co-wrote and directed called “Love & Bananas: An Elephant Story.”

In her directorial debut, Bell sheds light on the plight of the Asian elephant, a species threatened with extinction. Numbering just 45,000, the Asian elephant population has declined precipitously in recent years for a variety of reasons, mostly caused by humans. Having once roamed the Asian and Southeast Asian jungles freely, these elephants—smaller in size and in numbers than their African counterparts—are in trouble because their natural habitats are being destroyed by logging and deforestation. Further, these intelligent creatures are often captured and sold to circuses and trekking companies for tourists or used as service animals in the logging industry.

In her revealing documentary, Bell shows surveillance footage of the animals being abused and confined for days in what is called a “crush box” where they are chained and beaten to destroy their spirit so they can be trained to perform for humans. But there’s a bright side to the story. There are some organizations trying to save the species by rescuing Asian elephants from unspeakable conditions and bringing them to sanctuaries. One of these rescuers is Sangduen “Lek” Chailert, a Cambodian elephant conservationist, who has saved more than 200 elephants over the past 20 years. Time magazine has dubbed her a Hero of Asia. She and her team at the Cambodia Wildlife Sanctuary rescue abused and sick Asian elephants, rehabilitate them and allows them to live in the wild on a Cambodian preserve.

Bell had visited Cambodia once before to document the rescue of two service elephants—a male and female—but that didn’t work out. A few years later, the 31-year-old actress-filmmaker and her film crew joined Lek in an attempt to rescue a 70-year-old blind elephant named Noi Na, who like so many elephants in captivity, had been mistreated throughout most her life. The trekking company that owned her was finally willing to release the sick old elephant to Chailert. But first they had to go get her 500 miles away in neighboring Thailand.

The documentary explores that daring rescue operation, which was both complicated and dangerous as the elderly pachyderm is naturally frightened of boarding a truck. But with Chailert’s experienced hand and helpers, Noi Na eventually is coaxed onto the vehicle for the 23-hour journey to freedom at the sanctuary. Bell and her crew are there to chronicle every minute of the nail-biting rescue, which presents all sorts of hazards, including potential red tape as the truck crosses the international border and a frightened and blind and elephant that could faint at any moment from heatstroke in the jungle heat.

Bell is seen throughout as she interviews Lek and her rescue team and goes on the long and difficult journey to save the endangered animal, pouring water on Noi Na to keep her cool and petting her occasionally. Then there is the slow and careful process of introducing her to her new herd.

The actress spoke by phone about her debut documentary and how she hopes the film will inspire others to want to help save the Asian elephant from extinction. For further information, visit loveandbananas.com.

Q: What initially brought you to Thailand and Cambodia?

Bell: A family friend, David Casselman, who owns the Cambodia Wildlife Sanctuary, had been looking for 10 years with Lek to rescue two elephants to release onto the sanctuary. He finally found them and I got an email saying, “We’re going to release them. Anybody who wants to come and watch this can.” And it hit me. I said, “I have to film this. It’s going to be a short (film). It’s going to be a happily-ever-after story.” I pitched the project to Change for Balance Productions, which was onboard from Day 1. Before we knew it, we were in Cambodia.

When we got there, it was a disaster. The elephants were in horrendous condition. They were covered in abscesses and scars. They were malnourished and dehydrated. The forest was being illegally logged and poached. When I stepped off the plane, I asked what the smoky smell was and was told it from the clearcutting of the forest. Seventy-five percent of the Cambodian jungle—at least that was the percentage at the time—is gone. Through it all, I saw Lek fighting on the front lines with such hope to save the species every day. I knew that I had to use what I had at my disposal to tell this story. That’s when I decided to make this documentary.

Two and a half years later I brought my crew—three guys—when we went on the elephant rescue. For a documentary, it was extremely bare bones and guerilla. A lot of what we learned on the first trip was the sensitivity and care you have to have around the elephants. These elephants are extremely mentally and physically damaged. They’ve gone through years of abuse and suffering. For example, if we approached on one side of the Noi Na on the first day, she would get very upset. If the boom (mic) got in the way, or if we had an agenda, it wouldn’t happen. Knowing that, we all game-changed quickly, and made sure to get as close as we could and switch our gear to get us as close as we could for the audience, while being extremely sensitive to the elephants.

Q: Were there moments in the truck ride from Thailand to Cambodia where you wondered, “What am I doing?”

Bell: For sure. When Lek walked me through the truck before we (mounted the rescue), she pointed out the bed she made for herself and said, “We’ll be here with Noi Na because she’ll be scared and frightened.” Lek did not leave the truck—it was incredible.

When we first loaded Noi Na, she wasn’t eating or drinking and I had my hand on one of two beams that separated us from Noi Na, and Lek so delicately took my hand and moved it to the other side of the beam because she was afraid that Noi Na was going to crush my hand. It was at that moment that I thought, “What have I gotten myself into?” (She laughs.) It was a mix of, “Oh boy, I’m on this truck for the next 23 hours” and “How blessed and fortunate I am to have that seat next to Lek and next to Noi Na and to be able to tell this story?”

Q: How long were you at the Cambodian Wildlife Sanctuary once you retrieved Noi Na?

Bell: Only about a week and a half. The rescue happened immediately, pretty much the way it unfolded in the film. It happened within three days of when we landed. We packed a night bag and were on the rescue. We were there a week and a half afterwards for filming to see what would happen. Noi Na was in medical quarantine for about a month before she was released into the herd. They do that with all the rescued elephants to make sure they’re OK. That’s Lek’s protocol to make sure everybody’s safe.

I checked back with Lek, and it took a couple of months —sometimes it can take years for the rescued elephant to find a friend, and even then, it sometimes doesn’t happen—but it took her a couple of months and she found a friend. I learned last month from Lek that Noi Na has found a second friend.

Q: How is Noi Na adjusting to the sanctuary?

Bell: Lek calls her “a naughty old girl.” She has friends. She loves to swim in the river. She has a ton of energy. Lek told me that recently she’s been making a ton of noise in the evening, trumpeting and pounding around. They’re trying to figure out what it is. But as Lek said in the documentary, all of these elephants have gone through mental distress, so they’re psychologically damaged. To this day, Noi Na, when she eats food, she stands in one place and reached her trunk as far as she can, to get the food and eat it as though she is still chained. You can see in the film where she scratches he back leg with her trunk where a chain used to be.

Q: Is it like a phantom chain?

Bell: Exactly. Something like a phantom chain is so specific, so harrowing for this creature, which is such an intelligent and sentient being. The reason why captivity is so damaging is because they’re so intelligent that when left naturally in the wild, they travel miles and miles to forage for food and water and live and play and investigate, and when they don’t have that stimulation and access, and are in captivity, they begin to go crazy. You can see how it affects them acutely and specifically in every single elephant, just as it would a human. It was shocking to learn that.

Q: Audiences may want to know what they can do to help save these Asian elephants.

Bell: That’s a huge part of the release of the film. We launched an impact campaign. We’ve created our website—www.loveandelephants.com—to be a hub for immediate action. There’s a petition you can sign. You can sign a humane traveler pledge. Also, the key to saving the species is education, so we have social media resources that you can grab and post. When people know better, they do better. We’ve partnered with GreaterGood, which has launched The Love & Bananas Fund, inspired by the film. It’s currently raising money for Lek’s wish list and to get an elephant out of Laos.

It was my goal with this film to make change but to also make change accessible with the same spirt of hope and victory with which Lek works. It’s such an honor to partner with GreaterGood to do this.

Also, if “Love & Bananas” isn’t at a theater near you, you can bring it to a community with a community screening, an in-home screening or a school screening. We have the resources to bring this to an interested community, big or small.

Q: As a first-time filmmaker, what did you learn?

Bell: I just released an e-book called “Shoot it, Sell It, Show It: How I Made an Independent Film with Grit & Google.” I kept a journal of my experience for the past five years. And it’s all the tips, tricks and pieces of advice that I learned to help inspire other filmmakers, to help them and save them any heartbreaks that I went through.

I learned a lot from Lek, who has used the press and the media as her main form of dissent to protect herself and her work. She goes with a camera around her neck everywhere to document what’s happening to the elephants and herself. She has a film team with her as a form of protection. I’m so impressed that my generation and the younger generation, which is who we wanted to target, and make it appealing and fun, to see an animal movie. I want to introduce everybody to Lek. There are a lot of followers in this world, but very few heroes, and Lek is a hero of mine, so I can’t wait to get this message out there.